EDITED BY

CHARLES FRANCIS ADAMS.

VOL. I.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| v vi vii viii ix. | ||

| 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | ||

| 30 32 32 33 34 35 36 37 | ||

| 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 | ||

| 121 122 23 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 | ||

| 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 | ||

| 248 249 250 |

I TRUST I may be pardoned for offering some explanation of the form in which I have decided to put the present publication.

It is now six-and-twenty years since the event happened which devolved on me alone a grave responsibility as the custodian of a voluminous mass of manuscripts accumulated during seventy-five years of continuous service of two public men, father and son.

Of their value as materials contributing to the history of the rise and progress of the United States in its first century, I could not entertain a doubt. Their importance in elucidating a specific course of action, often connected with heavy responsibilities to the state, seemed equally obvious. Not insensible to the hazard attending their preservation in a country passing through social changes so rapidly as this does, and warned by well-known instances of dispersion and loss in other quarters, it has been my leading wish to place the essential portions of this collection intrusted to my care out of the reach of danger, by publication in my own day.

Moved by these considerations, I lost no time in entering upon my labors, by first preparing for the press a collection of the papers connected with the life and times of John Adams. This duty was fulfilled by the production in succession of ten large octavo volumes, requiring on my part the assiduous application of eight consecutive years. It is doing no more than justice to the liberality of the Congress of the United States, to recognize the assistance given to this part of the undertaking by a subscription for one thousand copies.

The next and far the most difficult part of the work yet remained. The papers left by John Quincy Adams were not only much more numerous, but they embraced a far wider variety of topics. Whilst the public life of the father scarcely covered twenty-eight years, that of the son stretched beyond fifty-three. Fully aware of the danger of losing time, if my design was fully to complete the task, I applied myself at once to the labor of reading for a selection not less than a preparation of materials for the press. But circumstances needless to detail just then interposed, which seemed to command my own services in public life at so wide a distance from home as to make a further prosecution of this plan for a time impracticable. Yet I may say with truth that, during this interval of nearly twelve years, the hope of returning to it was never out of my mind. And when at last relieved by the kindness of the government, at my own request, I hastened to resume the thread of my investigation just at the point where I had left it so long before.

The chief difficulty in the latter part of this enterprise has grown out of the superabundance of the materials. Not many persons have left behind them a greater variety of papers than John Quincy Adams, all more or less marked by characteristic modes of thought, and illustrating his principles of public and private action. Independently of a diary kept almost continuously for sixty-five years, and of numbers of other productions, official and otherwise, already printed, there is a variety of discussion and criticism on different topics, together with correspondence public and private, which, if it were all to be published, as was that of Voltaire, would be likely quite to equal in quantity the hundred volumes of that expansive writer.

But this example of Voltaire is one which might properly serve as a lesson for warning, rather than for imitation. No reader can dip into his pages in the most cursory manner without noticing how often a mind even so versatile as his repeats the same thoughts, and how much better character is understood by means of a single happy stroke, than by dwelling upon it through pages of elaboration.

The chief objects to be attained by publishing the papers of eminent men seem to be the elucidation of the history of the times in which they acted, and of the extent to which they exercised a personal influence upon opinion as well as upon events. Where the materials to gain these ends may be drawn directly from their own testimony, it would seem far more advisable to adopt them at once, as they stand, than to substitute explanations or disquisitions, the offspring of imperfect impressions painfully gathered long afterward at second hand.

It so happens that in the present instance there remains a record of life carefully kept by John Quincy Adams for nearly the whole of his active days, and in condition so good as but to need careful abridgment to serve the purposes above pointed out. It may reasonably be doubted whether any attempt of the kind has ever been more completely executed by a public man. The elaborate memoirs of St.-Simon, which fill twenty volumes, on the one side, and those of Grimm and Diderot, which make sixteen more, on the other, may be cited perhaps as similar examples of industry. But although each of these publications may perhaps have its points of superior attraction, they both want that particular feature which is most prominent here, the personification of the individual himself in direct connection with all the scenes in which he becomes an actor, and the examination to which he subjects himself far more severely than he does those about him. In this respect the contrast between him and St.-Simon is striking, as also in a superiority in aspiration for the good and the pure both in theory and action, which is more or less felt to pervade every page.

After careful meditation over the materials of this great trust, I reached the conclusion that it would be best to set aside the rest of the papers, and fix upon this diary as altogether the surest mode of attaining the desired results. Having settled this point, the next question that arose was upon the mode of making the publication. It was very clear that abridgment was indispensable. Assuming this to be certain, it became necessary to fix upon a rule of selection which should be fair and honest. To attain that object I came to the following conclusions: 1st. To eliminate the details of common life and events of no interest to the public. 2d. To reduce the moral and religious speculations, in which the work abounds, so far as to escape repetition of sentiments once declared. 3d. Not to suppress strictures upon contemporaries, but to give them only when they are upon public men acting in the same sphere with the writer. In point of fact, there are very few others. 4th. To suppress nothing of his own habits of self-examination, even when they might be thought most to tell against himself. 5th. To abstain altogether from modification of the sentiments or the very words, and substitution of what might seem better ones, in every case but that of obvious error in writing. Guided by these rules, I trust I have supplied pretty much all in these volumes which the most curious reader would, be desirous to know.

I am not unaware of the objections commonly made to publications of this kind, in their relation to opinions or action ascribed to other persons no longer in life to protect their own reputations, or who have left scanty means of rectification behind them. I fully admit the force of a remark attributed to a distinguished statesman, John C. Calhoun, in reference to any diary, that it carries conclusive evidence only as against the writer himself. Yet I cannot but add, on the other side, what is a fact remaining on record, that this eminent man, when attacked at a critical moment by bitter opponents, for certain acts done by him long before, did not hesitate to appeal to the writer of this diary, a colleague in President Monroe's cabinet, for reminiscences drawn from this very book, in his justification, and he obtained them, too. That a diary should furnish conclusive proof in any case can scarcely be assumed, in the face of the conceded infirmity of all human testimony whatever. The most that can be claimed for it is, that it shall be tested by the established rules applied to permanent testimony in all judicial tribunals.

Very fortunately for this undertaking, the days have passed when the bitterness of party spirit prevented the possibility of arriving at calm judgments of human action during the period to which it relates. Another more fearful conflict, not restrained within the limits of controversy however passionate, has so far changed the currents of American feeling as to throw all earlier recollections at once into the remote domain called history. It seems, then, a suitable moment for the submission to the public of the testimony of one of the leading actors in the earlier era of the republic. I can only add that in my labors I have confined myself strictly to the duty of explanation and illustration of what time may have rendered obscure in the text. Whatever does appear there remains just as the author wrote it. Whether for weal or for woe, he it is who has made his own pedestal, whereon to take his stand, to be judged by posterity, so far as that verdict may fall within the province of all later generations of mankind.

CHARLES FRANCIS ADAMS.

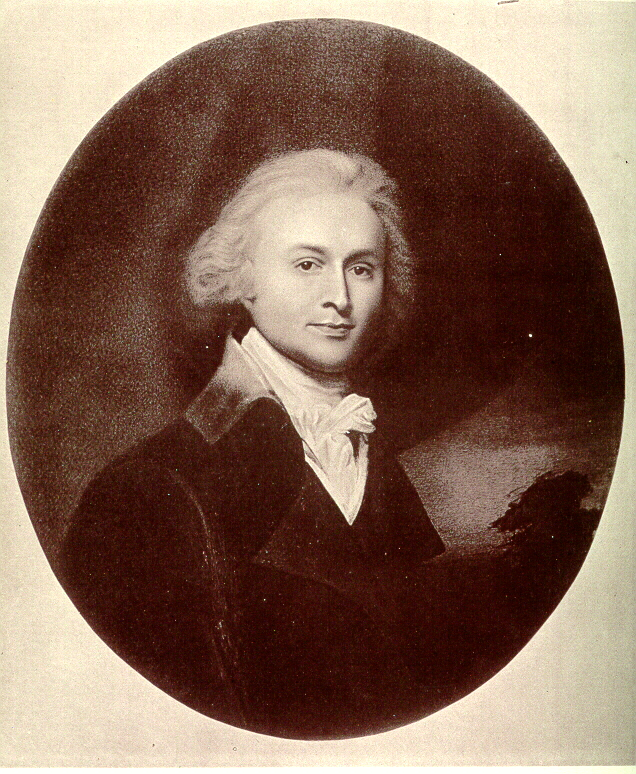

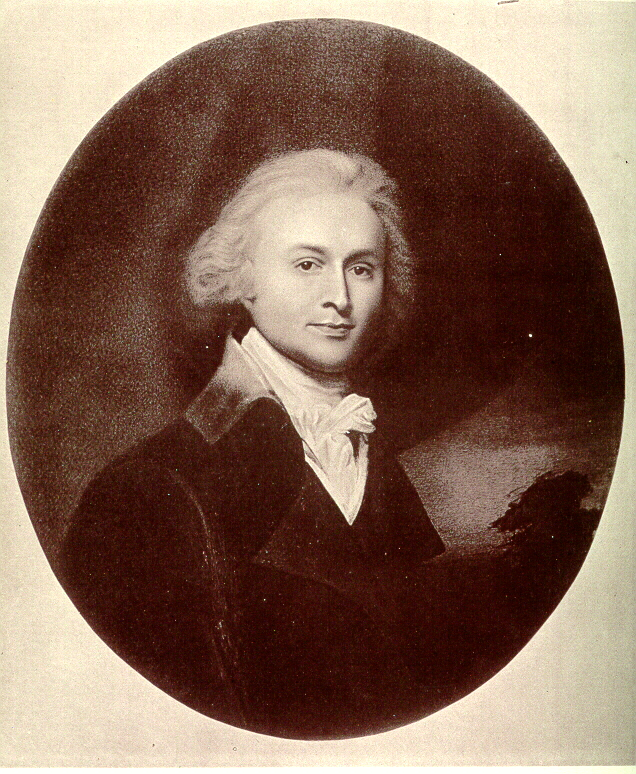

IT may reasonably be doubted whether any man ever left behind him more abundant materials for the elucidation of his career, from the cradle to the grave, than John Quincy Adams.

The eldest son of John and Abigail Adams, he was born on the 11th of July, 1767. The next day he received his baptismal name, at the instance of his maternal grandmother, present at the birth, whose affection for her father, then lying at the point of death, doubtless prompted a desire to connect his name with the new-born child. John Quincy was close upon his seventy-ninth year. A large part of his life had been spent in the narrow career of public service then open to British colonists in America. He had been twenty years a legislator, so far as the popular assembly had power to make the laws, and he presided some time over its deliberations. He had been in the executive department, so far as one of Her Majesty's council could be said to share in the powers of a governor deputed by the crown. And be had been a diplomatic agent, so far as that term could be applied to successful negotiations with Indian tribes. For these various labors he had received acknowledgments and rewards, the evidence whereof yet appears spread forth in the pages of the colonial records. The contrast in the scale of this career with that now to be shown of the great-grandson furnishes a notable illustration of the social not less than the political revolution which one century brought about in America.

Twelve days before the birth of the child, the pliable but not maladroit Charles Townshend, in the British House of Commons, had entered upon what Burke designates as the fourth period of the Anglo-American policy of that time. Not insensible to the chance of grasping the highest prize offered to ambition in his country,--a prize then dropping from the nerveless hand of Chatham, he bethought himself of a device which might at once win for him the favor both of king and commons. He would retract at least in part the mortifying concessions made to American resistance only the year before by the repeal of George Grenville's stamp act. He would re-establish the principle of taxation in a less exceptionable form. His plan met with favor, and, for a moment, nothing could seem more propitious to the fulfilment of his highest hopes. Unhappily, Townshend survived only long enough to know that the fruits which he expected to gather were to fall to other lips. But if Lord North was the person to enjoy the sweets, to him also was it reserved to taste the bitterness. And this sequence of events, involving the fate, not of that minister alone, but of myriads of the human race on both sides of the ocean, was to affect the fortunes of no single individual among them all more profoundly than those of the infant then lying in his cradle, in the little village of Braintree, in the Massachusetts Bay.

Seven years passed away, and the disputes springing from this root of bitterness grew higher and higher. They agitated no household more than that in which this boy was growing up. His father, from pursuing a strictly professional life, began to feel himself impelled more and more into the vortex of controversy which was ultimately to bring on the collision of opposite forces. His mother's temperament readily caught the rising spirit of popular enthusiasm in the colony, and communicated it to her child. Then came the first fearful conflict of armed men, the sounds of which spread even to her own dwelling. She took the boy, then not seven years old, by the hand, and they mounted a height close by, there to catch what might be seen or heard of the fight raging upon the hill but a few miles away. Thus it was that she fixed in his mind an impression never effaced to his latest hour. Only two years before he died he gave expression to this feeling in a letter responding to a complaint made by a highly respected English gentleman, a member of the Society of Friends, deprecating what seemed an unfriendly spirit to Great Britain, shown in one of his last public speeches, in a manner so characteristic that it properly finds a place in this connection. Thus he writes in 1846 to Mr. Sturge, of Birmingham:

"The year 1775 was the eighth year of my age. Among the first fruits of the War was the expulsion of my father's family from their peaceful abode in Boston to take refuge in his and my native town of Braintree. Boston became a walled and beleaguered town, garrisoned by British Grenadiers, with Thomas Gage, their Commanding General, commissioned Governor of the Province. For the space of twelve months, my mother with her infant children dwelt, liable every hour of the day and of the night to be butchered in cold blood, or taken and carried into Boston as hostages, by any foraging or marauding detachment of men, like that actually sent forth on the 19th April to capture John Hancock and Samuel Adams, on their way to attend the continental Congress at Philadelphia. My father was separated from his family, on his way to attend the same continental Congress, and there my mother with her children lived in unintermitted danger of being consumed with them all in a conflagration kindled by a torch in the same hands which on the 17th of June lighted the fires of Charlestown. I saw with my own eyes those fires, and heard Britannia's thunders in the battle of Bunker's Hill, and witnessed the tears of my mother and mingled with them my own, at the fall of Warren, a dear friend of my father, and a beloved Physician to me. He had been our family physician and surgeon, and had saved my forefinger from amputation under a very bad fracture. Even in the days of heathen and conquering Rome, the Laureate of Augustus C�sar tells us, that wars were detested by mothers, even by Roman Mothers,--'Bella matronis detestata.' My Mother was the daughter of a Christian Clergyman, and therefore bred in the faith of deliberate detestation of War, super-added to the impulsive abhorrence of the Roman mothers. Yet in that same spring and summer of 1775, she taught me to repeat daily, after the Lord's Prayer, before rising from bed, the Ode of Collins on the patriot warriors who fell in the war to subdue the Jacobite rebellion of 1745.

| How sleep the brave who sink to rest |

| By all their Country's wishes blest! |

| When Spring, with dewy fingers cold, |

| Returns to deck their hallow'd mould, |

| She there shall dress a sweeter sod |

| Than Fancy's feet have ever trod. |

| By Fairy hands their knell is rung, |

| By forms unseen their dirge is sung, |

| There Honour comes, a pilgrim grey, |

| To watch the turf that wraps their clay, |

| And Freedom shall awhile repair, |

| To dwell, a weeping Hermit, there. |

"Of the impression made upon my heart by the sentiments inculcated in these beautiful effusions of patriotism and poetry, you may form an estimate, by the fact that now, seventy-one years after they were thus taught me, I repeat them from memory, without reference to the book.1 Have they ever shaken my abhorrence of War? Far otherwise. They have riveted it to my soul with hooks of steel. But it is to war waged by tyrants and oppressors, against the rights of human nature and the liberties and rightful interests of my country, that my abhorrence is confined. War, in defence of these, far from deserving my execration, is, in my deliberate belief, a religious and sacred duty.

The year before the event here described, the writer's father, as is stated in this letter, had been commissioned as one of four delegates of Massachusetts to attend a Congress at Philadelphia, with a view to mature a unity of action among the colonies. From that time his absences from his family necessarily became frequent and protracted. It was during one of these that the incident took place. The boy on this account became naturally more and more of a companion, deeply sympathizing with his mother. Hence it was that in a letter to her husband, she tells him that, to relieve her anxiety for early intelligence, Master John had cheerfully consented to become "post-rider" for her between her residence and Boston. As the distance by the nearest road of that day was not less than eleven miles each way, the undertaking was not an easy one for a boy barely nine years old.

Of course, the few facilities for education then within reach were materially obstructed, and remained so, even after the scene of war was removed farther south. It does not appear that the boy attended any regular school. What he learned was caught chiefly from elder persons around him. Those of whom he saw the most, outside of the family, were three or four young men still preparing, under the tuition of his father, to fit themselves for the legal profession, according to the habits of that time. But they, one after another, fell off, taking commissions to serve in the war, until but one remained, a kinsman of his mother, by the name of Thaxter, who subsequently became his father's secretary during his second mission to Europe. To him John Quincy was indebted for assistance more than to any one else outside of his family. Yet, after all, the fact remains clear that without the exercise of his own earnest will he would have made little progress. What he felt on the subject can be best collected from his own words. Here is a genuine boy's letter written to his father. It is dated in the same year that he became post-rider. It is given exactly as it remains in his own handwriting.

BRAINTREE, June the 2nd, 1777.

DEAR SIR,--I love to receive letters very well; much better than I love to write them. I make but a poor figure at composition, my head is much too fickle, my thoughts are running after birds eggs play and trifles, till I get vexed with myself. Mamma has a troublesome task to keep me steady, and I own I am ashamed of myself. I have but just entered the 3d volume of Smollet, tho' I had designed to have got it half through by this time. I have determined this week to be more diligent, as Mr. Thaxter will be absent at Court, & I cannot persue my other studies. I have Set myself a Stent & determine to read the 3d volume Half out. If I can but keep my resolution, I will write again at the end of the week and give a better account of myself. I wish, Sir, you would give me some instructions, with regard to my time, & advise me how to proportion my Studies & my Play, in writing, & I will keep them by me, & endeavour to follow them. I am, dear Sir, with a present determination of growing better, yours.

P.S.--Sir, if you will be so good as to favour me with a Blank book, I will transcribe the most remarkable occurances I mett with in my reading, which will serve to fix them upon my mind.

The following year brought the great change which gave a turn to the rest of his life. John Adams was commissioned by the Continental Congress to take the place at the court of France forfeited by Silas Deane. This was in the hottest part of the war. He accepted the post, and on the 13th of February, 1778, embarked from the shore of his own town in the little frigate Boston, lying off in the harbor waiting for him. His son went with him. After a stormy voyage the vessel reached Bordeaux, and landed her passengers on the 1st of April, 1779. They procceded to Passy, in the environs of Paris, the place since made memorable as the residence of Franklin, but in which the other commissioners had also resided. Not many days were lost in putting him to a school close by, and here he acquired that familiarity with the French language which proved of such essential service to him in his subsequent diplomatic career.

He was eleven years old. It was then that the idea of writing a regular journal was first suggested to him. A letter to his mother, in which he explains himself, is of importance in this connection. It is given literatim:

PASSY, September the 27th, 1778.

HONOURED MAMMA,--My Pappa enjoins it upon me to keep a journal, or a diary of the Events that happen to me, and of objects that I see, and of Characters that I converse with from day to day; and altho. I am convinced of the utility, importance & necessity of this Exercise, yet I have not patience and perseverance enough to do it so Constantly as I ought. My Pappa, who takes a great deal of Pains to put me in the right way, has also advised me to Preserve copies of all my letters, & has given me a Convenient Blank Book for this end; and altho I shall have the mortification a few years hence to read a great deal of my Childish nonsense, yet I shall have the Pleasure and advantage of Remarking the several steps by which I shall have advanced in taste judgment and knowledge. A journal Book & a letter Book of a Lad of Eleven years old Can not be expected to contain much of Science, Litterature, arts, wisdom, or wit, yet it may serve to perpetuate many observations that I may make, & may hereafter help me to recolect both persons & things that would other ways escape my memory. I have been to see the Palace & gardens of Versailles, the Military scholl at Paris, the hospital of Invalids, the hospital of Foundling Children, the Church of Notre Dame, the Heights of Calvare, of Montmartre, of Minemontan, & other scenes of Magnificence in & about Paris, which, if I had written down in a diary or a letter Book, would give me at this time much pleasure to revise & would enable me hereafter to entertain my friends, but I have neglected it. & therefore can now only resolve to be more thoughtful and Industrious for the Future. & to encourage me in this resolution & enable me to keep it with more ease & advantage, my father has given me hopes of a Pencil & Pencil Book in which I can make notes upon the spot to be transfered afterwards in my Diary & my letters this will give me great pleasure both because it will be a sure means of improvement to myself & enable me to be more entertaing to you.I am my ever honoured and revered Mamma your Dutiful & affectionate Son

John Quincy Adams

Though the intention to commence this undertaking is thus declared, it does not appear to have been immediately executed. Six months had barely elapsed, and he had got well settled in his studies, when affairs took a turn which again broke up all regularity of occupations. His father, left without further public duties by the abolition of the French commission of three persons, decided to return home. The result was his acceptance of a passage in the French frigate Sensible, then ready to carry, to America the Chevalier de la Luzerne, the first French envoy to the new republic, and his secretary, Barb� Marbois. Landed safely at home, he had scarcely resumed his old habits when another call came from the Congress to cross the sea again. Only three months intervened before he and his son were once more on the way to France in the very same vessel that had brought them out.

This irregularity of life could scarcely be deemed favorable to the boy's progress in learning. And yet it probably advanced an apt scholar like him far more than systematic instruction would have done. He was brought at once into close companionship with men of culture and refinement, much older than himself, whose conversation was worth listening to. The French minister and his secretary, afterwards the Marquis de Marbois, as well as the naval officers attached to the frigate, took much interest in him on the outward voyage; and on the return, their places were more than made up to him by the presence of Francis Dana, then going out on his mission to St. Petersburg, and of his kinsman and home teacher, Mr. Thaxter.

It was upon the entrance on this last voyage that he made his first attempt to execute the plan marked out in his letter of the year before. It still remains, in the form of two or three small books of perhaps sixty pages in all, stitched together under a brown paper cover. The first of these is prefaced by this title:

1 There is but one error. In the fourth line of the second stanza, the word "watch" is substituted for "bless."